This text goes over the major points I discuss with designers who are making their first puzzle games. It summarises my process for approaching these challenges and highlights common pitfalls I tend to encounter.

This is an intro to a pretty wide genre. Keep in mind that when I mention puzzle games, I’m mostly thinking about games where logic challenges are the core and there’s a mechanical progression (The Witness, A Monster’s Expedition, Storyteller, Monument Valley, etc). Resident Evil has puzzles, but it’s not a puzzle game at its core. Monkey Island, while it’s mostly composed of puzzles, doesn’t show a mechanical progression (puzzles don’t share much between them beyond the point-and-click interactions).

Eureka!

Puzzles are all about logical reasoning and deduction. The “fun factor” usually comes when players follow a rational process to discover the right answer. That moment when the lightbulb turns on. Does getting to the solution always feel rewarding or engaging? Well, no, that’s the challenge. Creating a puzzle that triggers that Eureka moment. That’s one of our big goals.

A satisfying eureka

Why does one puzzle feel rewarding when solved while another can be tiresome? It can be a complex question. But there are two factors that play a big role here:

- Whether the deduction process involves new ideas or not: A solution that leads a player to novel and interesting ideas is more likely to be satyisfying.

- Difficulty: If a puzzle is too easy or too hard it can spoil the eureka moment or completely overwhelm players.

The balance between these two values is tricky. My personal opinion is that presenting something novel is more important. A puzzle that seems a bit too easy but still presents a new idea can still be engaging. More than a long and complex puzzle where the solution feels like homework.

Finding the needle in the hay

Imagine a branching tree with all the actions a player can do in a level. And how some actions lead to states where new actions become available (like removing an obstacle that lets players move in new directions).

When we present a level, we’re basically laying out this branching tree in front of the player and asking them to choose the right set of steps. And we’ll want that correct solution to be somehow obscured, making players stop and examine the puzzle elements.

But this game of finding the needle in the hay is rigged. Just trying every potential solution until we hit the correct one would feel like boring homework. As designers, we’re dropping small hints here and there for players to interpret. We can make a puzzle harder or easier by tweaking these hints to make them more subtle or more blunt.

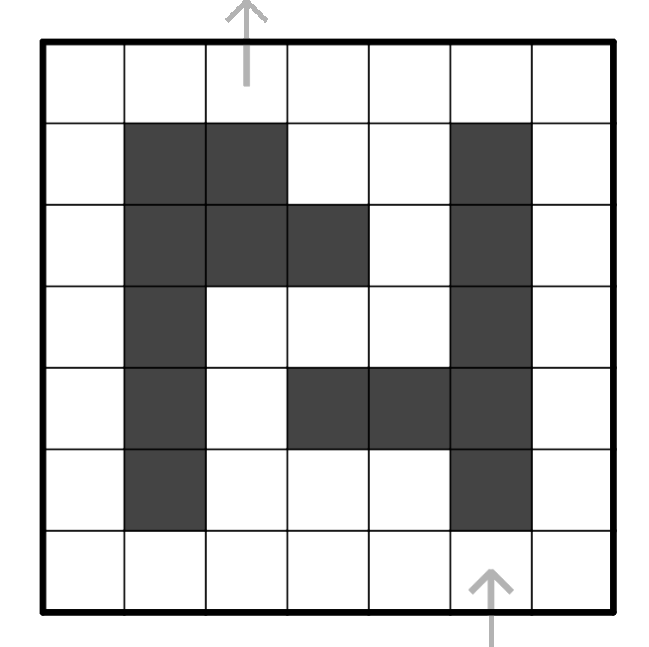

Consider the following puzzle:

The rules are:

- Players must trace a line that starts at one arrow, goes through all the empty cells in the grid, and ends at the other arrow.

- This line can never branch or cross itself.

If we start at the arrow at the bottom, we could consider several paths, but this level is plagued with all sorts of hints. One of the basic signs this layout shows is that, if players start by heading left, they’ll create a dead end (which would make it unsolvable, since the path can no longer go through that cell before reaching the other arrow).

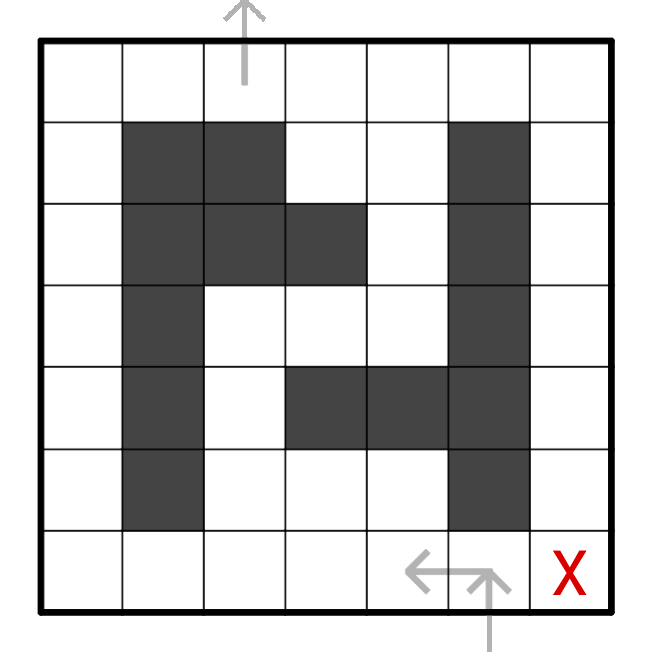

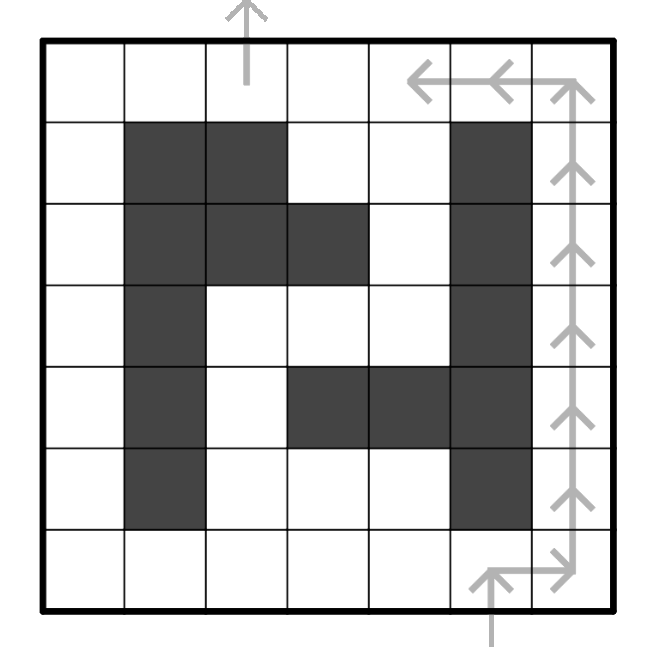

Once players interpret that hint, there’s only one viable path, which takes them to the next decision.

Here they can apply the same process to find the next steps.

This is a fairly simple example, but it can be abstracted and applied to other puzzles and situations.

- Players are presented with a set of rules and a desirable outcome.

- Initially, many viable paths seem to be present.

- But when the rules and elements are examined, players can draw conclusions from them (example: “dead ends lead to the puzzle not being solvable”) and apply those findings to prune the tree of options (example: “I need to spot which decisions lead to dead ends and avoid them”).

If drawing those conclusions and applying them to the puzzle feels interesting/engaging (which I realize can be vague words) then we’re on our way to creating a satisfying puzzle.

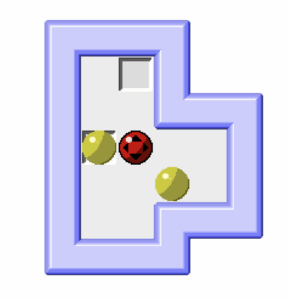

Sometimes solving (and even designing) a puzzle is easier when we start at the solution and walk back from there. Consider the first level in Microban 1, a well-known example in the puzzle community. It follows the basic sokoban rules. Players control the red ball and they must push the yellow spheres into the sockets.

The usual way to solve this is to start with the desired end position. We know the sphere on the left can’t reach the other socket (because we can’t push it to a different column). So the solution must be found by trying to get the other sphere to the upper socket (and tackling the obstacles that appear as we do so).

What makes an idea interesting

This is a term I’ve brought up a few times, and it can be quite abstract and highly personal (depending on your past experiences, something could be novel or familiar). Our brain finds discovering some ideas pleasing, but it doesn’t happen 100% of the time. Let’s go over two very rough examples.

- 123 x 456 = ??????

This problem derives from a system you already knew (multiplication) and it’s more complex than the sort of calculations people do everyday. But doing this operation doesn’t usually trigger any satisfying feelings. It’s mechanical and has that homework feel I mentioned earlier.

2. Now consider this puzzle made by Draknek. I recommend trying to solve it before moving on.

I’ve forgotten my 4 digit passcode!

Fortunately, I saved some hints on my phone. All the hints have a yes/no answer. I remember that if you know all the answers then you can determine the passcode, and that there are no redundant questions.

The hints are:

– Is the first digit 1?

– Is the second digit 2?

– Is the third digit 3?

– Is the first digit even?

– Is the fourth digit larger than the sum of the first three digits?

Unfortunately, to access the answers to the hints, I need to log in to my phone with my passcode 🙁

You’ve probably seen this sort of “crack the code” system in the past. In videogame, escape rooms and so on. You’ve probably seen harder puzzles within this framework. But it introduces several ideas that feel refreshing. Like the fact that the hints are questions with a yes/no answer. But the cherry on top is (spoilers ahead) realizing “there are no redundant questions” is key for solving it. At first glance, that sentence doesn’t look extremely useful, but later you see nuances in that statement. And discovering those nuances and corners hidden in what seemed plain and explored tends to be quite satisfying.

Common pitfalls

Some common undesirable situations to watch out for.

- Puzzles where players don’t understand the goal right from the start: In some specific cases it make sense to obscure what the player should achieve to complete the puzzle, but in vast majority of games, this is something that needs to be 100% clear from the start.

- Puzzles where there aren’t any meaningful choices: Imagine a room with an exit door I’m trying to reach, but it’s high and I can’t get to it. The only element within my reach is a button. When the button is pressed, it raises a platform that allows me to reach the door. There was only one thing I could do and it wasn’t really a meaningful choice.

- Puzzles where executing the solution is tedious: Sometimes the solution of a puzzle has many steps (examples: “moving items around several times” and “having to walk long distances to interact with the puzzle elements”). If the puzzle solution is spotted with a quick glance, but then the execution has the player doing a lot of busywork, that can get tiresome fast.

- Puzzles where the mental load is overwhelming: Puzzles that ask players to calculate moves many steps ahead while keeping track of several objects. They expect players to keep a big amount of information while considering their next choice, and that can be overwhelming, especially in puzzles that involve tricky things to visualize (like rotating objects).

- Puzzles that are just too hard: This one is extremely common and I find myself falling into it again and again. Sometimes we see a player going through our levels quite fast and we feel the urge to tweak the puzzles to force players to stop and look at it for a longer time. There are some situations where it makes sense to add an extra twist to a level, but it’s extremely common to end up pushing levels to a point where they are less enjoyable.

For every rule there are a few exceptions that work, but I feel these are good recommendations to follow until later on, when you have a better grasp of the base concepts and decide to break them deliberately.

Quick break

How are we doing so far? These concepts can be quite abstract and a bit overwhelming at first. It’s a complex topic, even though we’re only focusing on a tiny space within puzzles and we haven’t even talked about major points such as designing mechanics. Have patience and remember to take this at your own pace.

Defining your mechanics

This tends to be the number one question when it comes to designing puzzle games, but it’s hard to tackle without understanding the concepts we saw above. That satisfying exploration of ideas is what we are chasing. If our mechanics don’t create those interesting choices with hidden corners to explore, then we need to iterate them.

I think when you are starting out, it can be frustrating to try to find a set of mechanics that lead to good puzzles. As you make puzzle games, you develop an intuition about the depth of a mechanic. You’ll still have to prototype and test it, but that intuition helps you discard lots of mechanics early on. I believe the best way to developer that intuition is by working with proven frameworks (like grid-based puzzles or logical deduction puzzles) before attempting to do something from scratch.

I tend to use the second level rule for discarding mechanics early on. Let’s say we have this concept for a 2D puzzle platformer where the character can turn into a ghost and go through walls. The goal is to reach a door in each level.

That sounds exciting from a narrative point of view. Going through walls to activate passages or disable hazards. It’s easy to picture a first level where players learn this ability and use it to reach a door. But what about a second level? What kind of challenge or new idea will the second present? And the third level? If nothing comes up, that mechanic is probably a shallow one. Sometimes it just needs further iteration (like some limitations or a different level goal), but I don’t prototype a puzzle mechanic until I have at least 3-4 levels in mind.

Just remember that some ideas might have a very appealing narrative implication, but that doesn’t mean it’s nuanced enough.

Okay, I have a mechanic, how do I make the levels?

There’s a common misconception I hate about puzzle design, the idea that you have to be some kind of math/programming prodigy to come up with the levels. When you play a finished level in a puzzle game, you are just seeing the end result, you are missing the exploration work the designer did to get there.

We’ve established we’re trying to create interesting challenges and those require nuanced ideas hidden in our set of mechanics. Our first task is to explore our system and try to discover what’s behind the surface. Many puzzle designers use that word “discover” because it feels as if you were just finding something that was there all along.

I tend to go to the level editor and create different situations. Nothing really specific. Just playing around with shapes and distributions. Then I play around considering what I can do and what feels interesting. I’m looking for gold nuggets. Something that hints an Eureka moment. Maybe it’s a situation where I realize that if I added/changed/remove an element it’d lead to an interesting level. Once I’ve found that, it’s time to polish it.

Consider the game Portal, a puzzle game where you can shoot portals at floor/walls and move between them. One of those gold nuggets within the system is that portals could keep momentum. You could fall through a portal and exit through another with the speed you had during the fall.

That’s a nuance, a side of our mechanics that we didn’t perceive on a first glance. Then we try to figure out what details of that nuance we want to enhance. We can also add layers on top of it. We can make gaining inertia a puzzle itself before players get to use it to solve the main challenge.

Not all gold nuggets are as flashy as this one. Maybe your gold nugget is how in a grid-based puzzle, you need to stand in a certain side of a box before pushing it. If you find it interesting, it’s worth trying to turn it into a level. Removing the annoying elements around it and presenting it to players in a way that is more engaging.

Expanding mechanics

In many cases, you’ll want to expand your mechanics with new behaviours that help you design more levels.

Most puzzle designers tend to approach these situations with a very minimalist philosophy. Adding only something that expands the core ideas into something adjacent to them, a natural extension.

In 2018 I designed a puzzle game called Bleep Bloop. It used a fairly common mechanic (when players press a button, the character slides in that direction unable to stop until they hit an obstacle). My core twist was that you were controlling two characters (and you needed to coordinate them to solve the puzzles).

That idea only carries you a certain distance, then you need new elements or rules. In this case, I decided my new mechanics would take the basic mechanic (sliding around) and add new options and possibilities to it.

So in the second world you encounter a gum that lets you stop in the middle of a movement (expanding the choices available) and, later on, you also discover levels with parts that can be toogled on/off, and blocks you can manipulate more freely (each of them grows that space of potential actions).

When trying to decide how to expand your mechanics it’s always important to consider if they’re bringing enough interesting options to the table and how they’ll combine with your existing ones. I like having some sort of creative compass that helps me decide the direction I’d like to expand (in the case of Bleep Bloop, that was the movement).

Tutorials

There’s a special kind of level we haven’t covered yet. Levels where a new mechanic is introduced to players for the first time. When I’m tackling these, there are two things I’m aiming for:

- Creating a space where the player can just interact with the puzzle elements and discover this new rule on their own. I try to avoid direct explanations, but sometimes there are good reasons for including them.

- Making it a puzzle. Ideally, the whole challange of that level shouldn’t just be to understand the new mechanic, but to solve a small puzzle using it.

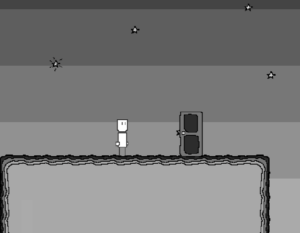

In 2020 I made a small game called Party Animals. This is the second level in that game. Players control the bear but they haven’t played a level with other animals yet. As they move around they’ll discover other animals “stick to them” when they step close. Once they’ve figured that out, they still need to discover how to use that new rule to get the platypus and the penguin to the highlighted cells.

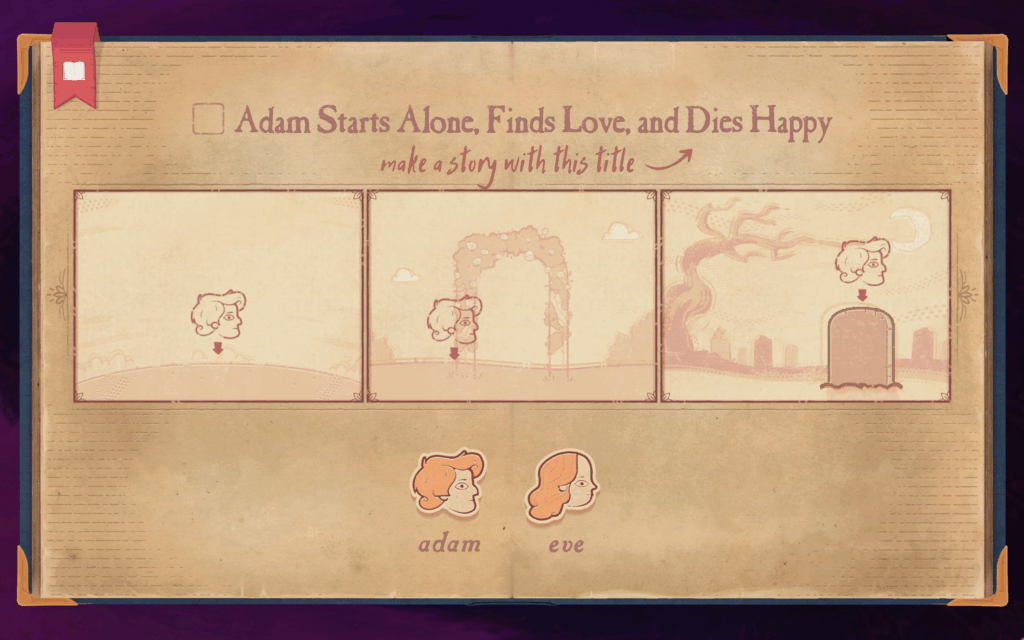

This is the very first level in Storyteller. It’s introducing quite a lot of things at the same time. The goal of the game (highlighted with a direct explanation) and the main mechanics (dragging characters around and how a story evolves). Once players have understood the mechanics and followed the explanations, there’s still a short puzzle to solve before completing the level.

Final thoughts

There are countless ways to approach the design of a logic puzzle. For those taking their first steps, I’d recommend the following:

- Look for a established sub-genre or framework that appeals to you and it’s not hard to produce. It could be sokoban games. Sudoku-likes. Line-drawing games, etc. Spend about an hour researching different games in that space to get a rough idea of how designers are exploring that space.

- Try to come up with a twist. You can just write down random ideas and then consider if they’re a good twist. Like “what if sudoku had letters instead of numbers?”, well, that wouldn’t really change the puzzle, but then you can consider some additions, “and you needed to make sure a certain word appears in each region”. Try to spot if those twists add enough depth.

- Explore your sets of mechanics. Try to find at least 3-4 gold nuggets that you think are fun to discover.

- Then make a level using each of those nuggets. Think about what needs to be added/removed to really make it shine. Consider “pruning” alternative solutions that might lead players to complete the level without considering its core idea.

- Put your levels in order, think about the progression between them, and give it a final structure. Then publish it and see how players interact with it. You’ll learn a lot by seeing players going through your levels.

And as always, I’d highly recommend aiming to make something in under 3-4 days. Even if it’s not very polished, you need player feedback to get a better understanding of these concepts and delaying it will slow your progress in the end.